reflection

I am sitting in compartment B on an unremarkable train in one of Serbia’s minor outlying villages, somewhere along its twisting eastern border. I share the compartment with my sleeping wife (face mirror-like with sweat), two backpackers from Australia, and two older Serbian women. Marisa and I were originally meant to be in the compartment next door, but when we embarked the train early this morning in Belgrade our reserved seats had been claimed, along with their attending four, by six burly men who informed us that paid reservations were not particularly meaningful in “this country.”

Just as well, as our companions in compartment B have been perfectly amicable, if not particularly sedentary. Since joining the train about an hour back, the two Serbian women have been fidgeting almost constantly: now rising to rearrange their baggage (they have lots of it); now shoeing us out of our seats so they can stand on them to better reach the overhead luggage racks; now looking out the window; now navigating through tangles of legs to peek out the door. Since stopping at the border, they have been particularly disinclined to sit still. Just now one of them gives me a wink after standing on the seat next to me in order to stuff a black bag up behind my backpack; should I be worried?

Perhaps the fidgeting is brought on by the heat. Supposedly 102 degrees outside, it’s probably a little hotter in here: the sun has been beating in for some time, and only a shoestring breeze finds its way through the crack in the window that I’ve managed to prop open with the rocks; like all the windows on this train, it’s ingeniously made to spring shut if nobody’s holding it down. Behind the rock and the crack in the window is a ticket office plastered in Coca-Cola stickers; the images of ice-cold refreshment seem at this moment unnecessary, and cruel. And so I sit and dream of ice as we wait for border control, and permission to continue on into Bulgaria.

In some ways things have changed quite a lot since the start of our European journey… then it was cold and overcast; then the trains moved faster and went further; then ice-cold refreshments and air-conditioned compartments were a consistent reality (even if made unnecessary by the cold weather); then trains left on time, and seat reservations meant something more. But the scenery then had not been as spectacular, the countryside had not felt as close, and those train rides on balance had not been as memorable.

Waiting to depart from Belgrade station.

Then there are the things that have remained constant as we’ve trekked across the continent. Namely Coca-Cola. A significant irony as there were few things Europeans feared more, wanted less, or were more unified in protesting in 1947 (when Coke opened its first bottling plants in France), than the “Coca-Colonisation” of the continent. This I have learned from Tony Judt’s fat book on Europe, Postwar, a history since 1945. Fat books are good for long train rides; this one has lasted through several.

Which makes me consider my trip now that I’m here at the end, in the sun, on these last tracks, waiting for a final stamp in my passport. In a few days the traveling part of my oh-so-weird project will come to an end… after more than three-hundred days on the road, seventy of those spent here in Europe, I will halt in Amman and make games. Routine, something which seems remote and imaginary--even exotic--from my current position in space-time, will enter my life again. In Amman I will wake, take a shower, sit down at a desk, and spend the rest of my day hitting keys with my fingers in an attempt to bring ones and zeros to life. What will my binary daydreams be like then? What will I remember of all this?

Oxford. Port Meadow and Ot Moor and all the fabulous spaces sprinkled ‘round the shire. There aren’t spaces like those where I’m going. There aren’t spaces like those where I’ve been. Spaces to walk through freely no matter who owns the land, spaces to breathe in, spaces where the first dinosaurs were dug up and named.

Port Meadow, Oxfordshire.

Communal living at Darvell. Walking down a path that first night and coming upon two octogenarians examining craters in the moon. Songs and dances, vegetables and discussions of faith… everyone happy to see us, everyone glowing like Moses.

View from our room at Darvell; welcome cards and cookies in the foreground.

Game-jamming at Cambridge. Meeting Stephen and Terry and Alan and all those friendly indies. Testing games and speaking code, and having people understand.

Jamming hard in Cambridge.

Paris in the rain. That apartment with its small balcony and graphic novel of Genesis, so exactly like my preconception of what a Parisian apartment should be like, yet tactile and thick with history. The Louvre being too big to look at, and too good for English. The Eiffel Tower hiding away till we found it and jumped. Competing with Karith and Marisa to find invaders.

An invaders spotted in Paris. Marisa found that one.

The names of people in Belgium, sounding as friendly as they were; Hucky Gillen and Inge Hernie. Talks about Afghanistan, and going back there. Following Inge to a fake beach on the river where we waited for the sun to set, then froze to death while watching Once Upon a Time In Mexico on a giant outdoor screen. Chasing down building-sized comic strips in Brussels. Drinking hot cocoa at the Grande Place and thinking that it was, and is, the best old square in Europe. Learning that everything French is Belgian. Finding Magritte, and Saint Bavo Cathedral: the church I most want to go back to. Eating baklava with Tale of Tales.

One of Brussels' many comic strip murals.

Meeting our landlord in Amsterdam, whose vast collection of old computer games bonded us instantly. Finding my favorite painting in the world and staring at it for an hour: the real thing so much more vivid and quiddative than its many reproductions. Cars that made Smart models look fat.

Van Gogh's Sunflowers.

Berlin, the seat of the middle of Europe: how it brought home all the wars I’d been reading about in a way that stayed with me through the rest of our trip. Pieces of wall, Checkpoint Charlie; half a century of a divided country, continent, and world.

View from Berlin Tower. The Reichstag can be seen in the distance.

Staying with Petr Kotouš in the Czech Republic; talking about computer games and poetry; introducing him to the indie scene while he introduced me to walking beer. Sitting with Marisa on Castle Hill, watching a rainbow come out after the rain, and thinking that Prague was perhaps the most beautiful city we’d been to. Smoulove craziness in the old town square… a craziness that followed us everywhere in Europe.

View of Prague from Castle Hill.

The architecture of Vienna: elegant, bold, and regal. Discovering Hundertwasser, his rejection of straight lines, his proposal of tree tenants. Coffee and streusel, schnitzel and cake.

Vienna.

Budapest. St. Stephen’s Basilica, with its interior almost too golden to look at, and the withered hand of Hungary’s first king off in a corner, sitting there in the dark till someone dropped fifty cents to light it with neon. Hiking through the heat of the city, then wandering into a cave church and feeling the cool air wash over us as we listened to a mass begin. Talking into the night with Ildiko and Peter Rozsovits about everything from color theory to Nazi occupation… an occupation still evidenced by bullet holes in the house where we stayed, a house built by Ildiko’s father, which had once been far out in the countryside though now its surrounded by city.

Interior of St. Stephen's Basilica.

Leaving tourists and air-conditioned trains behind as we headed towards Zagreb. Meandering through Mirogoj cemetery and feeling no disappointment at its beauty, though I had been warned that it was one of the world’s most impressive burial grounds. Stumbling into a Franciscan church on the way home that wasn’t marked on our map as anything special, yet turned out to be one of the best churches I’ve ever been in: not giant, but splendid--while somehow still humble and earthy; no sound but the gentle rustle of robes as a priest went about his duties; no light but the rainbows cast by stained birds and fishes and beasts of the field. And next door the city cathedral, once considered the furthest reach of Western Christianity; thick walls were built to defend it from Turks, if it came to that.

Ban Jelacic Square, Zagreb.

Being picked up at the train station in Sarajevo by an ancient man in an ancient Citroën that was easily twice my age. Getting to our hostel, sitting down in the garden, and listening to the owner talk for two hours about the history of his people, a people nearly snuffed out in the ethnic war that ended only fifteen years ago. “Nobody cared,” he told us, “Not the EU, not the UN… only America saved us.” The first time in my life I had heard (in first-person) a non-American speak in favor of any kind of U.S. military action overseas.

Cemetery for victims of the four year siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War, just around the corner from our hostel.

Then only two days ago there was a night in Belgrade with our couch surfing hosts and their friends… some beers and some laughs, and Vladimir playing his trumpet. Walking by the biggest people I’ve ever seen as we strolled through city streets. Sitting on a piece of old fortress and watching the sun set where the Sava and the Danube meet. Waiting as lights turned on, and young people came out to play basketball beneath those same old fortress walls. Sleeping, then boarding a last train.

Night basketball in Belgrade.

And now here we are at Bulgaria’s border.

And now something funny has happened.

Across from me one of our Serbian friends has pulled up her shirt just slightly, and is unwrapping from around her waist a nylon stocking which she’s tied there. And in the stocking are packs of cigarettes. And now the other woman pulls down the black bag that she hid behind my backpack earlier. More cigarettes. They continue reaching into their clothes.

The police have come and gone, with passport control, and now all along the train people are scurrying madly, jamming fingers into secret holes, sticking arms up to elbows between places that really shouldn’t have a between. And all of the holes, and all the betweens contain cigarettes: packs and packs, cartons and cartons. It looks like Marisa and I, and the Australian couple in our compartment may very well be the only people on the whole train who didn’t depart Belgrade as smugglers.

As we start our slow chug towards Sofia the train settles down; indeed, the women in our compartment have undergone a remarkable transformation since recovering their last treasures from pant legs: they sit still now, and smile contentedly while chatting quietly together. I can’t help but smile contentedly myself. I started writing this piece with some idea of having a grand reflection, of getting at the meaning of the trip, the meaning of travel, the meaning of Europe and me. And I’ve failed to do anything but reminisce. But right now that’s enough for me. Right now this train ride is enough for me.

Towards Sofia...

Related slideshows:

Waking up in the village of Sungai Batu, at the Southern tip of Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, is the same every morning: you wake up with the sound waves that call the faithful to prayer. The prayer, if you are not Muslim, is optional, but the waking up is not: Sungai Batu is small, and every bedroom in every residence inside the village lies within easy striking distance of the loudspeakers mounted on the central mosque's minaret.

Sungai Batu at sundown.

And so it was for us, every day for a week. Then something odd happened, on the last day of our stay. That morning, as the final verses of the Adhan faded and I rolled over to renew my slumber, another sound caught my ear... a strange sound... a sound that seemed to clash with the first. I sat up, and turned my head to listen. It seemed as if this new sound were also coming from the mosque, just as the call to prayer had done... except... except...

Except the sound was the sound of Justin Bieber's voice, singing "baby, baby, baby, oh!"

I am the kind of person who easily waxes nostalgic for times gone by... I romanticize bygone eras of exploration and discovery, and allot most of my daydreaming time to imagining myself as a daring globe-trotting archeologist born about two hundred years ago.

I also indulge my nostalgia with literature. As I traveled through Malaysia, for instance, I spent some time reading a bland contemporary account of the overarching history, but spent a good deal more time lost in the pages of a nineteenth century travel diary penned by a woman named Isabella Lucy Bird. Not content with the expectations for her gender in Victorian England, Isabella set out with her "Gladstone bag and canvas roll" to visit America when she was twenty-five, and spent the rest of her life crisscrossing the globe, from Morocco to India, Turkey to Japan. She ended up funding her adventures by publishing her detailed letters and diaries, which remain some of the most insightful travel writings available from the period.

Isabella Bird photographed in Tibet, a few years after she traveled Malaysia.

When Ms. Bird came to Malaya by steamer in 1878, British colonies had been established on the islands of Penang and Singapore, and the peninsula's outline had been roughly mapped; the interior space however, was nothing more than a black hole as far as most Europeans were concerned, and the peninsula itself was still referred to by the name Ptolemy had given it sometime in the second century C.E.: "The Golden Chersonese."

Ms. Bird set out for Malaysia from Hong Kong, then steamered her way to Saigon and Singapore before approaching the mysterious peninsula itself. This is where I was in my reading the night before I woke up in Penang to Justin Bieber's voice.

No horse for me, but a 'moto' proves the next-best way to traverse Penang.

Romantics like myself, comparing our experiences to those of people like Isabella Bird, sometimes complain that contemporary travel is stale. That the world has grown too small, too quickly, and that "alien experiences" are few and far between. That there is nothing new to witness, or discover on this planet. That we are living at the wrong time for "interesting" journeys.

Justin Bieber--of all people--reminds me that such claims are wrong.

Such claims are wrong because never, at any other point in history, has Isabella Bird or any other traveler been able to experience what I did in Sungai Batu. Never before, in Malaysia or anywhere else, has Bieber followed the call to prayer. We are living at a time of fantastic temporo-cultural juxtaposition, and while one can experience this juxtaposition anywhere, it is only by traveling that one starts to grasp the extent of the "mashup" that is occurring around the world, and perhaps gain some new perspective for what it all means.

An American like me, for instance, might see mosques being built in New York as a kind of "invasion." In Malaysia, though, we find a new normal: one in which mosques are everywhere and Muslims make the law. We may be put at ease to hear familiar pop music playing outside our hotel window after the Adhan, but being in Malaysia, it's impossible to ignore the notion that the Malay woman in a hijab eating breakfast next to us probably views the whole situation—from New York to Bieber—completely reversed.

A mosque in NYC.

Bieber aside, there is a deeper level at which listening to the Adhan in Malaysia is fascinating. It is fascinating because five times a day, in the heart of Southeast Asia, one can stop and listen to to the ebb and flow of Arabic verse conceived hundreds of years ago in an alien culture located half way around the world. And that is just the beginning of this country's astounding multicultural heritage. Pick a street in Georgetown or Malacca, and you've got a pretty good chance of being able to walk by a mosque (built by Malays, Arabs, or Indians), Buddhist temple (built by Chinese), Hindu temple (built by Indians), church (built by Chinese, Indians, or European settlers), and colonial fortress within the space of one or two city blocks... all of them but the fortress alive and active with worshipers.

Fort Cornwallis was present in Georgetown long before Ms. Bird. visited... the clock tower behind was built soon after she left to commemorate Queen Victoria's 1897 Jubilee.

Only fifty percent of Malaysia's population is in fact comprised of ethnic Malays... and the Malays themselves are not indigenous to the peninsula or Borneo. Ten percent of the population is indigenous, with the rest being of Chinese or Indian descent... the offspring of generations of immigrants who came to work the tin mines, plant the fields, and set up business--many of whom were "shipped in" by the British.

The citizens of Malaysia are governed by two courts: one which handles all secular cases, and everything related to the ethnic Chinese and Indian populations, and another--the Islamic Sharia court, imported from Arabia--which governs the Malays, who are Muslim by ethno-religious state definition. The majority of political power is held by Malays, while the majority of the country's wealth is held by ethnic Chinese, and the majority of laborers are ethnic Indians.

In short, Malaysia is one of the most heterogeneously multicultural countries in the world. Cultures have been colliding here for a very long time. In fact, the more I saw of Malaysia, the more I realized that--Bieber notwithstanding--I was encountering many of the same things that Isabella Bird had encountered over a hundred years ago, from the cultural juxtaposition, to the friendly people, to the lush open jungle, to the equatorial heat, to the amazing variety of delicious foods.

Having dinner with Kian--a Malaysian of Chinese descent who hosted us for two nights in Ipoh.

Most importantly, my journey was similar to Isabella's in the way that all journeys will always be similar: we both encountered something of what a particular place is like right now (which of course includes something of what it was like in the past).

As far as I can tell, the world is always changing. We gain some things, and we lose some things, but I think it's important not to be too nostalgic about the past, not to privilege getting to see an "uncorrupted" culture over getting to hear Justin Bieber play in a small town in Asia. Because those uncorrupted cultures never really existed; culture is a discussion, and we've all been having it for a very long time. I tend to agree with what Ovid said some two-thousand years ago: Omnia mutantur, nihil interit ("everything changes, but nothing is truly lost"). People like myself complain about the world getting smaller, but I think that we're humbugs and liars, because the world, if anything, is getting bigger. Go back a hundred years, and ask yourself how likely it is that you would have had the resources (or inclination) to travel out of your home country. Now ask yourself how likely it is that those villagers in Sungai Batu would have had the resources to travel out of theirs. All of us get to experience more cultural diversity now, in the twenty-first century, than we ever could have hoped to do at any point the past.

I think there is room for a mitigated skepticism in all areas of life, and I think that, in the coming decades and centuries, it is imperative that people take strong stands to safeguard the precious parts of their cultures, because there is a danger that some precious parts may be washed away. But that doesn't make the wave inherently bad, nor does it make travel in the contemporary world "boring." On the contrary: every day, all over the world, more people than ever before are coming into contact with new modes of thinking, new forms of living, new ways to be who they are, and new ways to be who they aren't... are coming into contact with people and styles and ideas that their parents never could have imagined. People are trying to figure out what to keep and what to throw out, trying to decide what's valuable and what's trash, trying to change and trying to stay the same. Sometimes it's ugly, sometimes it's violent, sometimes it sounds like a prepubescent pop singer I really wish would go away... but as I sit here in Kuala Lumpur listening to the Korean pop megahit "Nobody" play in the background, with an amazing sampling of Indian food in front of me, at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant that sports a large "like us on Facebook" sticker on the wall... I am reminded that most of the time it's just messy, and crazy, and a whole lot of fun watch--and be a part of.

Social networking advertised on a city bus we took from Sungai Batu to Georgetown.

Related slideshows:

“Cambodia is like Australia.”

I had been sitting on a boat in the sun all day, coming up the Mekong from Vietnam, and all those rays were making my senses feel a little bit baked. I couldn’t be quite sure if the words I thought I heard came from inside or outside my head.

“Come again?”

“Cambodia is like Australia,” Rob repeated. “People are super laid back here, and friendly. They work hard—really hard—but they know how to kick back and relax hard too, at the end of the day. I love it.”

Rob, an Aussie himself, has been living in Phnom Penh for the last several months, where he unexpectedly set up house after cycling his way up from Singapore on a recumbent tricycle and deciding not to leave. We connected through CouchSurfing.org, and he generously offered to host Marisa and I while in Cambodia’s capital… which is how I came to be sitting on his couch nibbling sweet mango while he compared the Southeast Asian nation I had just crossed into with his homeland down under.

I’ll admit that the comparison caught me by surprise. I didn’t know much about Cambodia before visiting, but the little I knew about the Khmer Rouge regime dominated my mental image: I pictured a country under a dark cloud, devastated and depressed, struggling to recover from untold horrors. Australia, on the other hand exists in my mind as a rather more happy and sunny place.

I still haven’t been to Australia, but after four weeks in Cambodia I can say that the people we’ve encountered here have indeed been incredibly laid back and friendly. People seem to smile with their whole faces on a more regular basis than I remember them doing elsewhere, and this, along with the constant performing of sampeah (bowing with palms together) creates a disarming effect. The sampeah came naturally to me (probably because of all the bowing I did while in Korea), and I caught my smile getting constantly broader under the barrage of friendliness. Soon I found myself entering into easy conversation with all kinds of people: with a woman selling cane juice by the side of the path on a rural farming island outside of Kompong Cham, who taught me several words of Khmer through signs; with a shop vendor who turned out to also be a high school teacher studying English when and where he could—we had a forty-five minute dialogue about our two countries and exchanged emails at the end of it; with Sa Vorn, our tuk-tuk driver in Angkor—a hard-working man who exudes honesty and trustworthiness… and with many others. One highlight was dining with Rob along with his Cambodian fiancé’s family, his future brother-in-law chatting away with us vigorously in pigeon English, alternating questions, jokes, laughter, and directives to “eat more frog legs!” faster than we could keep up (the frog legs, fried with lemon grass and chili, were delicious).

Dinner with Rob and his bride-to-be (before other family members showed up).

So what of the dark cloud? What of the Khmer Rouge? As I learned more about the regime I was shocked to discover that the horror was—if anything—worse than I had previously imagined. In the four years that “Red Khmer” controlled Cambodia, over two million people died from starvation, torture, and brutal killings—a full quarter of the country’s population at that time—making the period deadlier on a per capita, per nation basis than the American Civil War or the Rwandan Genocide.

An image painted by one of the few S-21 prison survivors.

Pol Pot’s communist “revolution” was the most radical ever attempted, making the Soviet and Chinese programs look sensitive and gradual by comparison: in 1975 all foreign ambassadors were evicted, schools and hospitals were closed, banking, currency, and private property were abolished, and religion, romance, and family loyalty were outlawed in one fell swoop without any kind of gradation schedule. Cities were turned into ghost towns as residents were driven into the countryside to perform fieldwork, where they were expected to produce incredible rice yields on meager rations (though many of them were lacking the most basic agrarian knowledge). Power was placed in the hands of the “pure” peasants and children, who were taught to obey all orders and use force indiscriminately, while former city dwellers and “educated elite” were considered corrupted beyond redemption, and thus expendable (excepting party leaders like Pol Pot, who were generally the best-educated of all).

One boy who was arrested then tortured and killed at S-21.

This was the high point of the regime. As the city dwellers failed to produce great quantities of rice, everything got worse. Rations were decreased below starvation level while work hours were prolonged, and violence escalated. Pol Pot, unable to believe that his revolution could fail, suspected corruption within the party. Cadres and lieutenants were arrested and sent to Security Prison 21, where they were tortured until they confessed to working for the KGB, CIA, or Vietnamese government. Then they were asked to name fifty more conspirators (who were predictably brought in next) before they were taken to the killing fields. Their wives and children, charged “guilty by blood,” were also killed (the children usually by beating their heads against trees). These killings were mostly carried out by "pure," barely adolescent teenagers. In the countryside the educated were asked to step forward for “forgiveness,” then beaten to death, while everyone everywhere starved. If the Khmer Rouge had not antagonized Vietnam to the point that the Vietnamese army invaded in 1979 to topple the regime, it is likely that the Cambodian population would have been totally exterminated within a matter of two or three more years, Pol Pot left alone in his utopia, atop a monstrous pile of skulls.

Skulls of victims at the Choeung Ek killing fields.

This is what the kind, smiling, laid back people here have been through. Since the deadly regime was toppled things have been infinitely better in the sense that people aren’t dying by the thousands, but in many ways Cambodia is still in the early stages of recovery. It took decades to rid the country of the last Khmer Rouge insurgents (whom the American government supported gainst the Vietnamese into the 1980s, and who were active into the mid-90s), and the country is still littered with millions of land mines laid to keep those insurgents at bay. Despite a UN attempt to promote fair elections in 1993 the current government remains an offshoot of the one installed by the Vietnamese in 1979, rather than the people’s choice, and is largely irresponsible and unresponsive, making little attempt to meet its nation’s basic health and education needs, relying instead on foreign aid (much of which seems to vanish as it enters the country). Corruption is rampant and widespread (with Transparency International ranking the country in the bottom 1% in their worldwide corruption index). Many former Khmer Rouge leaders and cadres are in powerful positions in the current government, and many more live ordinary civilian lives, having never been asked to account for past deeds. In 2006 an international tribunal was established to try the most senior KR leaders, but it has met with numerous bumps in the road, and only one person has been convicted to date, with their sentence now being appealed.

After the bows and the smiles and the gracious hospitality, these realities did come out in my discussions with Cambodians. In hushed tones people asked me if I had visited Choeung Ek, then explained how they were attempting to process the horrors of their country’s past. “How could this happen?” They asked me. “And why?”

As if I could provide any answers.

“This past is not taught in our schools,” said Sa Vorn gravely, before going on to tell me of Cambodia's widespread corruption and how it affected his job, along with other grievances he had with the government. Then he smiled, picked up the English grammar book that he spends all his spare time studying, started up his tuk-tuk, and drove us on to the Bayon… one of Angkor’s largest and most impressive temples, built by Cambodia’s most beloved King at the height of their empire’s splendor. The sun was just rising, and there was not another soul in sight.

Sa Vorn, studying his English while he waits for us at a temple stop--no kidding, that's a grammar book.

And this has been my experience of Cambodia. Learning about one of the worst autogenocides in human history while interacting with some of the nicest, most laid back people I’ve ever met, in the shadow of a staggeringly majestic bygone era. I don't know if Cambodia is like Australia, but it certainly isn't like any place I've ever been.

This, again, is why I travel.

The Bayon at sunrise.

Related slideshows:

Bonus! A few interesting facts about Cambodia:

- Buddhism is the professed faith of 95% of Cambodia's population, which is the highest percentage of Buddhist believers in the world (tied with Thailand). All Cambodian men over the age of sixteen are expected to serve some time as monks as a kind of right of passage.

- Cambodia's chief cultural influence is India, rather than China.

- Unlike neighboring languages like Thai, Lao, and Vietnamese, Khmer is a non-tonal language.

- While Cambodia has its own currency (the Cambodian riel), its use is limited mainly to pocket change, with the country's main legal tender being the US dollar (which all ATMs dispense--at amounts up to $2000 per go!). Generally you pay for things in dollars, and get any change less than $1.00 back in riel.

- Cambodia is the cheapest place in the world to buy certain electronics, notably Apple products, high-end cameras, and other items with relatively determined retail values. Prices are typically equal to their counterparts in the United States (where electronics are still cheaper than most "hyped" locations in Asia due to market differences), but have the advantage of being completely untaxed to everyone.

- Cambodians like their beer with lots of ice. Which of course makes sense for a country with Cambodia's climate.

A few weeks ago I wrote a glowing review of the experiences Marisa and I had while traveling in Taiwan… a jovial celebration of the vulnerability of extended travel, and the wonderful encounters that come out of it. I made a game called “The Kindness of Strangers,” dedicated to all the nice people who helped us along our way. I emerged from Taiwan radiant, optimistic, almost high on the joys of traveling, and the general decency of the human race, excited to continue on and get high all over again in Vietnam.

I suppose I was being naïve. The idea of living life in a perpetual high, whatever brings that high on, is rather ridiculous. Because highs are called “highs” for a reason: if even a small percentage of the population could maintain them indefinitely, they would be called “flats” or simply “life general.” Highs are balanced by lows, and slopes in between. People can’t maintain highs because the world is not of one kind, is not all abundance: a certain drug might make me feel happy, but eventually my supply will run out; I can stuff myself full of food on Thanksgiving Day, but still someone in North Korea will die of starvation; I may encounter ten ridiculously kind strangers in miraculous succession, but turn a corner and I will encounter someone who isn’t so nice. And of course, vice versa. The world is neither white nor black, abundance nor lack, good nor evil, but a mixture of both; in the vocabulary of Asia (and the lens through which Neil Jamieson examines Vietnam's culture and history in his excellent textbook): yin and yang.

All of this seems ridiculously obvious as I write it, but for me it’s important to remember, because I am prone to extremism, and placing a disproportionate amount of weight in whatever experience I’ve most recently had, or happen to be examining at the moment: this thing that I’m experiencing right now, this is what the world is like. And so my most immediate experience becomes a lens that colors my entire perception of the world, prejudiced greatly over previous experiences I may have had. (Incidentally, I recently finished reading Daniel Gilbert’s rather interesting psychological “detective story,” Stumbling on Happiness, and it appears I’m not alone in this behavior: in general, people seem to be incapable of accurately remembering past experience, and how it made them feel, over the way current experience makes them think that past experience made them feel)

I begin with this perhaps-tedious philosophical drivel, because the encounters Marisa and I have had in Vietnam were by and large so strikingly different from the encounters we had in Taiwan, and I have been trying to make sense of that difference, and also to keep some kind of perspective.

In Taiwan, it seemed that everywhere we went people were simply ridiculously nice to us. So consistently nice to us, that by the time we had been there a couple of weeks we came to expect it, and we let our guards hang low all the time: when the first truck we hailed on the east coast pulled over to hitch us, we didn’t hesitate to throw our bags in the back before we got in ourselves (though we “knew” we should take basic precautions, we just couldn’t bring ourselves to feel cautious at the time, must less suspicious), and when a man in Hualien offered to drive us to the bus station because taxis were rare, we didn’t even think to ask him how much money he wanted (because no one who had helped us had ever wanted any--and he was no exception), never mind thoughts of anything worse.

In Vietnam, by contrast, it seems nearly everyone we’ve met has wanted something of us, and in some cases they’ve been prepared to take it whether the item in question was offered or not. “Friends” have turned out to be mercenaries, and strangers to be swindlers, most of them fairly aggressive. A lot of this “swindling”, mind you, has been unexceptional and--somewhat ironically--simply taken the form of aggressive, unfettered capitalism: guest houses quoting us prices in US Dollars, then insisting on a ludicrous exchange rate if we didn’t settle it ahead of time; taxi drivers setting their meters at the wrong price point because they thought we wouldn’t notice (then getting angry and aggressive when we wanted to disembark); hotel managers selling us $5 bus tickets that actually turned out to be worth 50 cents on packed minibuses full of vomiting children; or, at the start of it all, the government charging us a seemingly arbitrary price for our visas as we entered the country (then shortchanging us when we didn’t have the exact amount they wanted).

On one level, it’s obvious that none of these interactions constitutes “pleasant” by definition; but on another level, it’s hard for me to fully articulate (or defend) why they bother me, when I feel that I should have expected them all. Vietnam is a very poor country, and with ninety million citizens, it ranks thirteenth on the global population scale. The economy, while one of the world’s fastest growing, is still small; per capita GDP sits at a meager $1,100, and prices are low. In this context, next to the average Vietnamese, I am probably not quite a billionaire, but a solid millionaire at least. Why shouldn’t I pay more for a taxi, or a bus ride? Why shouldn’t I give tips out for everything? I’m in a communist country, after all, so why shouldn’t people use their capitalist wile against me for the socialist end of redistributing wealth? Such activity may be inconsistent and unregulated, but it serves the same purpose that a wealth tax does in developed western nations. The idea, in theory, doesn’t bother me.

Nor does the actual monetary loss. Indeed, our net loss in all this swindling amounted to nothing more than a small mound of pocket change (well, maybe a big mound, but still: pocket change). The idea of contributing something to the Vietnamese economy--as someone of relative wealth passing through the country and availing myself of that economy--actually appeals to me. I want to contribute.

What bothers me, I guess, is the way that everything happened: the feeling I was left with after all these encounters. The feeling that I’d been cheated out of money I didn’t even care about by someone I was hoping to have an amicable interaction with. The feeling that people were sometimes taking great pains to hoodwink me, when I would have gladly paid them more had they asked in a nicer way (or at all). But of course, you can’t buy friendship, and anyway I suspect the unfortunate reality behind many of our encounters was the simple fact that most of the people we interacted with needed money more they did friends.

Another fact to take into account is that most of the negative encounters we’ve had in Vietnam have been with people “of the trade”: people in the business of dealing with (and hustling) tourists and travelers on a regular basis. Vietnam has been on the backpacker trail for a long time, and the country is narrow, which makes it difficult to get off the dreaded “beaten path.” There’s still plenty of wonder to be had on that path (I’ll get to that in a minute), but it’s probably not the best place for authentic, endearing encounters with ordinary Vietnamese. In Taiwan we never gave much thought to getting off “the path,” because we never felt like we were on one: the journey felt more like a journey, and less like a scuttle from one carefully prepared tourist trap to the next.

Finally, in the interest of full disclosure as I describe my perceptions, I will say that towards the start of our time here (while we were still in Hanoi, visiting with Marisa’s family), Marisa’s sister’s hotel room was burgled as she slept; and towards the end of our journey, in Ho Chi Minh City, my camera was stolen out of my hand. I relate these incidents only for full disclosure, because I am well aware that my camera being stolen is more reflective of my own silliness (venturing into the chaos of Tet in Saigon with anything of value) than it is of any part of Vietnamese culture or society. There are thieves everywhere, just as there are kind people everywhere, and I know this. But as we travel, we don’t encounter the objective, we don’t encounter what we know, we don’t encounter statistics. We encounter a unique, bizarre, subjective train of events, that color and change us whether we want them to or not, which is my point. I think as travelers it’s important to realize that, important to admit it.

The police report for my camera's theft... not an easy task to acquire (but necessary for an insurance claim)!

When my camera was stolen out of my hand, in that mass of people, all of whom seemed to be after me (I had physically caught three people going into my pockets before the camera was tugged out of my grip), that moment seemed to me to epitomize my experience in the country. Later, as we waited for a city bus to take us to Saigon’s inter-city terminal, I watched pickpockets hawk their wares to locals, right in front of my eyes (watching hopefully, resentfully for my camera), and I was stunned that no one seemed to care (why should they? A foreign millionaire loses a watch to a poor resident thief... reasonable redistribution, right?). At that moment, that moment seemed to epitomize my experience in the country.

And in some ways it did. But of course in other ways it did not. Despite all these negative encounters I’ve touched on, there were naturally (and happily) moments to balance, moments to bring perspective. Our interactions with people generally did not leave us with the rosy glow that our encounters in Taiwan did, but there were noteworthy exceptions. For example, towards the end of our trip, in the Mekong Delta, a young man we met online offered to take us for lunch with his girlfriend. He was on leave from university in Saigon (for Tet), and was insatiably curious about our travels. We had a wonderful interaction over some delicious street food, and at the end of our meal he presented us with a hand drawn portrait of Marisa and I he had sketched from our photos online (and he didn't want money for it!).

Later, in Can Tho, another university student offered to host us for two nights in her tiny shack of an apartment where she lived with her sister… her “beautiful apartment” she called it, and it was. She insisted on giving us her bed, and smiled like our intrusion was the best thing that ever happened to her. We went out for smoothies with one of her university friends (who was translating Hawking in his spare time “for fun”), and the discussion we had with them while sipping down delicious fresh fruit was one of the highlights of our entire trip. These bright, friendly, optimistic individuals were an amazing contrast to the people who’d recently been ripping us off, and talking with them (about everything from anthropology to astrophysics to politics to American Idol to Facebook and censorship) helped bring needed perspective to our journey.

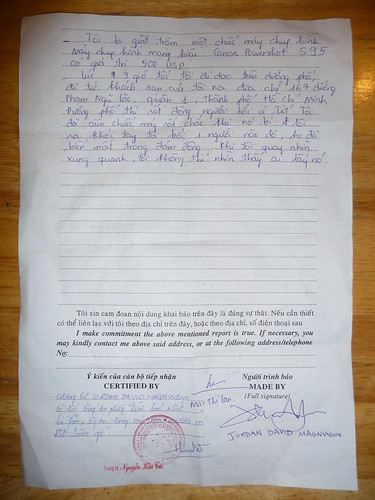

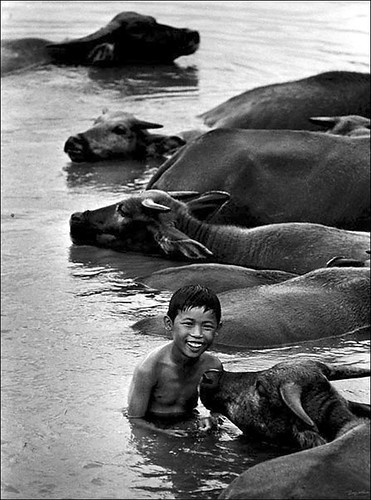

Or there was our encounter with Long Thanh: Vietnam’s most celebrated photographer. While in Nha Trang we went looking for his studio, as Marisa and I are both rather keen on photography; we were especially curious to see some of Mr. Long’s more famous works that we’d heard about, like his photo of a rural Vietnamese boy running across the backs of several submerged water buffalo, which (like many of his pictures) has won him a number of international awards. When we arrived, the studio seemed to be closed (it was Tet-eve, after all), but when we knocked, a young woman opened the door. We took our shoes off and went inside, appreciative of the cool air and quiet surroundings. The space consisted of three consecutive wooden-paneled rooms, lined top-to-bottom with black and white photographs. Long Thanh has been in the business of picture taking for over fifty years, but he has only ever had one subject: Vietnam, and he has only ever envisioned her in black and white. The large print photos were stunning.

Photo copyright Long Thanh.

Still, the real joy of the visit came later on when an older man entered the studio, and began talking with the young woman we had already met, as she showed him something on the hefty digital camera she held in her hands. After a moment, the man took the camera and held it up for us to see a photo of two sleeping cyclo drivers on its rear display: “my daughter took this picture just this afternoon,” he beamed. To make a long story short, the man turned out to be Long Thanh himself, and the woman his daughter. They wanted to keep the gallery open over Tet, so Long’s family was coming to him (his home, he explained, was just upstairs from where we stood). Over the next twenty minutes Mr. Long offered us interesting anecdotes about several of his photos, and before we left we made sure to ask for his best advice for budding amateurs like ourselves; his answer was hardly surprising: he told us to keep our eyes open.

Or there were the chats Marisa and I had over breakfast with a Vietnam War veteran who was staying at our hotel in Saigon; a Michigander who had fathered two Amerasian girls during the war. He told us how he had come back twenty years after the fighting to find them; how he had been wrenched with guilt when he discovered that the older of the two had been murdered, but how he found the other and was reunited happily with her. Now he has a house in Dalat, and was only in Saigon to settle some paperwork before being married to his Vietnamese fiancé.

Besides these happy interactions, there were Vietnam’s natural and historic wonders to inspire us, and those moments of being in a place and feeling amazed to be there, to be traveling, to be alive:

Flying through the countryside in the early morning in Ninh Binh on the back of a moped, watching rice farm after rice farm wiz by, then bam: a giant vertical karst emerging from the center of one of those rice fields. Then another. And another.

Whipping around one of those rocky monoliths and catching site of mammoth Bai Dinh Temple, in the process of being built… soon to be the largest Budhist complex in Vietnam.

Walking around Hue’s Citadel in the light morning rain, no one else there; the flowers and the moss on fire from the rain, burning green instead of yellow or orange; tiles glistening and shimmering; old moats threatening to overflow… a perfect morning to get lost in a fascinating old structure that’s been to hell and back.

Days on the train, feeling connected to generations of travelers who have gone before, who have sat and looked out the window and listened to the clak-a-ty-clak of iron horse wheels as one place turns into another.

Related slideshow: Vietnam Top 10 Train and Bus Shots

Taking the night bus from Hue to Nha Trang. A miserable experience, but an experience nonetheless. Travel doesn’t feel right to me unless there’s some discomfort involved at least some of the time.

Arriving tired and sore in Nha Trang at 5:00am, but feeling joyful as I watched the sun rise over the beach as locals exercised, before catching a few more zzz’s and diving into the five-foot waves.

Finally, I can say that some of the swindling we were subjected to actually lead to a few of our most memorable and interesting experiences. For example, I complained about being sold $5 “tourist bus” tickets for 50 cent “anything but” bus rides earlier, but again, my main grievance was with the way such transactions happened; taking packed local transportation, while not the height of comfort, is an experience I’m happy to have, and the local Vietnamese minibuses are amazing in the way they operate: they have advertised destinations, but will take anyone any part of the way between their two endpoints. People don’t wait for the bus: rather, each one has a worker who hangs out the door, calling out to everyone who passes, and metaphorically and literally pulls people into the fun (and not just people, but goods as well: one bus we were on picked up a large delivery of strong-smelling mushrooms). The main rule of thumb on these busses is that there is no such thing as “too full.” I wasn’t lying about the vomiting children either: one young tyke very narrowly missed a headshot opportunity that would have made the experience even more memorable than it already was.

And this, probably, is as good a place to end as any. Vietnam has offered us mixed experiences, but even those experiences that weren’t particularly comfortable or fun have still been experiences. Travel isn’t about the good things, or the bad things: it’s about all the things that happen to you while you’re in another place. It’s about trying to make sense of what you can, but ultimately, I think, about simply accepting the sum total, which will inevitably be more than can be analyzed or synthesized (and analysis and synthesis, valuable as they are, are not equal to and cannot replace the raw experience itself).

I started this post by reflecting on the negative interactions we’ve had here, not because I feel a lasting dislike for Vietnam, and want to vent some kind of revenge, nor because I think such interactions represent this country in any kind of holistic or objective way. Rather, I started the post the way I did because I am writing about the subjective experience of travel, and as we leave Vietnam the difference between the way we were treated on average here, to the way we were treated in Taiwan--and the effect that difference had on us--is too striking a part of our personal journey to overlook.

It is not about “Taiwan vs. Vietnam,” but about our particular experience in visiting Taiwan, and then Vietnam: because it’s impossible to travel without context, without a “before,” and an “after.” It’s about the fact that I left Taiwan rosy and optimistic, carefree and trusting, and that--despite the good times I’ve recounted--I am leaving Vietnam feeling somewhat cautious, suspicious, and cynical, with an eye to protect what is mine. This change in me is what I think about as I leave this place, and I ask myself, why? Why was our experience so different here? Was it the poverty? Was it the tourist trade? Was it our lack of effort in getting off the beaten path? Was it our unreasonable optimism and naivety brought on by the ridiculously positive experience we had in Taiwan? Was it the distorting lens of significant negative events, like having my camera stolen? Were we just unlucky? Was it all in our heads?

I suspect a bit of all of the above. Whatever the answer, our experience is what it is, and I don’t regret it. Sometimes travel makes me feel like I’m living on a cloud, sometimes it brings me back down to earth. Such is life. Such is the world. And that’s what I’m traveling to encounter. Whether inevitable or not, our experience in Vietnam was in many ways simply a balance to our experience in Taiwan, and I believe that balance is almost always good: yin and yang. What will Cambodia be like?

Related slideshows:

Related resources:

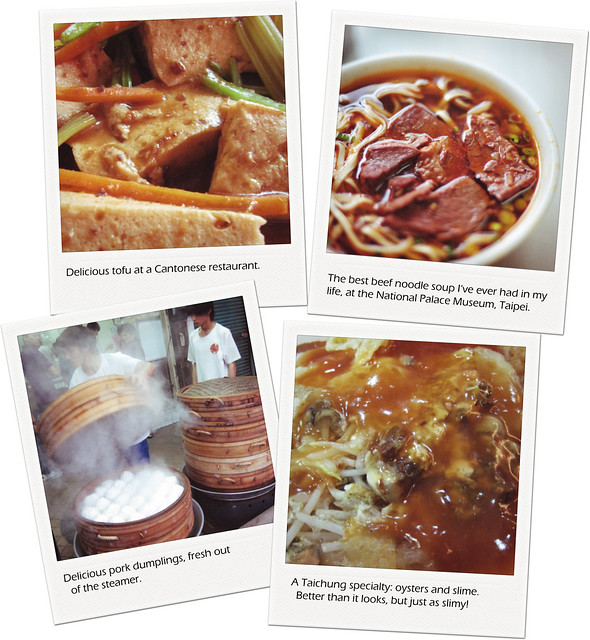

I will remember many things about Taiwan.

I will remember being wet, a feeling that characterized much of the first half of our trip. Walking around Taipei in raincoats every day for a week. Waking up at Fulong Beach to the sound of rain on canvas, enjoying the sound, then slowly coming to realize that the reason my head was cool was because our tent's waterproofing had failed under the relentless downpour. Waiting for the rain to stop, only to have it start again as we hiked through the jungle; making covers for our packs out of garbage bags. Being happy to finally make it to a Buddhist temple where we could spend the night and take refuge under a solid roof.

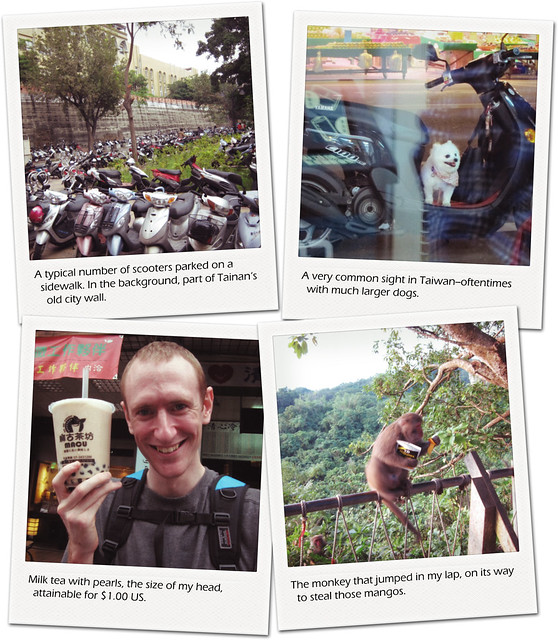

I will remember Taiwan's beautiful and remote east coast. Hiking the historic Caoling Trail and not minding the rain, because the climb made us hot, and because our surroundings were gorgeous... being surprised at the drastic change in vegetation as we gained altitude. Seeing a truly giant spider outside a small trail-side shrine, dedicated to one of Taiwan's host of Taoist deities. Spending the night on the beach at a small lighthouse village; waking up to the sight of seaside cliffs, and our first sunny day. Hitching a ride later that day in the back of a pickup and thinking there was nothing better than the breeze in my hair, the sun on my face, and the ocean view beside me. Watching monkeys leap through the trees at Taroko, and being surprised that the famous gorge actually managed to live up to its hyped reputation.

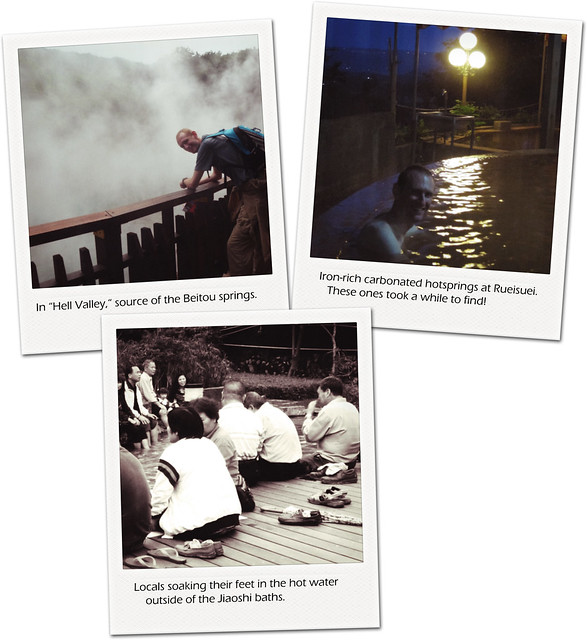

I will remember the hot springs. The feeling of hiking around Taipei for days on end, then finally letting my body drop into the hot water of Beitou, an outdoor bath where we watched the sun set along with locals who went there every day. Sitting in the splendid wooden baths at Jiaoshi that exuded feng shui; baths which a Taiwanese man informed me were so nice "because the Japanese built them." Getting off the train at Rueisuei and walking for miles through farmland in an attempt to track down Taiwan's only naturally carbonated springs; thinking we were lost, then finally making it to the Rueisuei Hot Spring Hotel, where we were the only guests of an eclectic Taiwanese family that loves Harley Davidson. Showering in iron-rich spring water that turned our hair orange.

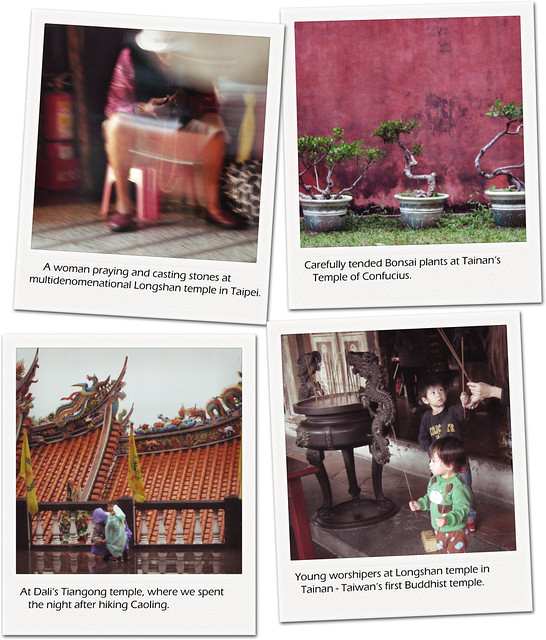

I will remember Taiwan's myriad temples and shrines, Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucius; the Taoist temples overflowing with color and ornamentation, gaudy yet earnest... their Confucian counterparts stark and simple by contrast, manifesting the teachings of old Master Kong. Everywhere we went, no matter how remote, or how busy, somewhere close by incense was burning, somewhere close by someone was bowing in prayer. On the hiking trail, next to a tree: there was a shrine; in Taroko under a bridge: there was a deity waiting; across from a farmer working the fields in Hualien county: there was Matsu, face black from decades of incense.

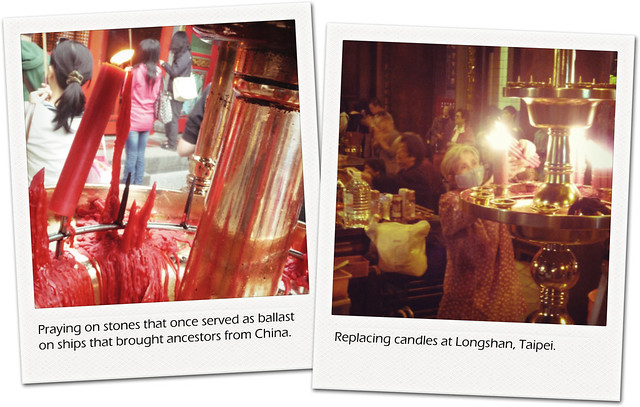

The temples are tactile places: rough wood pillars sprout up from rough stone floors, large iron pots for incense are cool to the touch, giant wax candles are smooth and shiny to look at; smoke rises in puffs, chants float on the wind, and inside a doorway, through the haze of the incense, you can make out the shapes of fruits and candies which gods like to eat. To your right a woman cleans cubic feet of wax from cubic feet of candles; to your left, a man gives incense to his three year old daughter and tries in vain to guide her in its use. And that is why I love the temples: they are so old, so alive, and there's so much going on; they are places where sitting and waiting, watching and listening, waiting and touching are greatly rewarded--there's nothing quite like running your hand across a stone that ten thousand people have stood on to pray, that served as ballast on a ship bringing immigrants from China 300 years ago, in a country that's made up of ethnic Chinese who don't consider themselves part of the Mainland.

I will remember so many "little" things (if one is heartless enough to give memories sizes): more scooters than I've ever seen before, more dogs per capita than I've ever seen before, more dogs on scooters per capita than I've ever seen before. More bubble tea, cheaper bubble tea, better bubble tea, and more kinds of bubble tea than I have ever drunk before. More monkeys jumping in my lap than have ever been in my lap before. More stinky tofu than I've ever smelled before. More helpings of chicken feet than I've ever eaten before, and also of New Zealand oatmeal (oatmeal making a cheap breakfast, being very popular in Taiwan, and much of it imported from New Zealand).

I will remember the food.

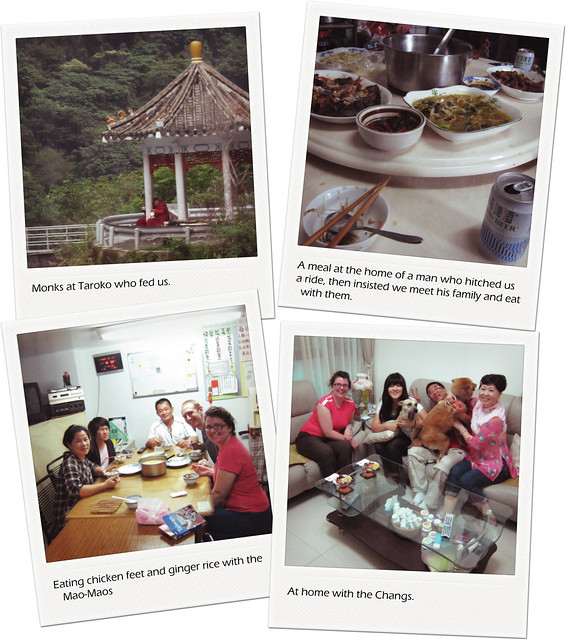

And I could go on. But of all the memories, the ones that I will recall most fondly are of all the times that people helped us; all the times that strangers were kind to us without reason. In Taipei, getting lost, and a woman offering to help us as soon as my map was halfway out of my pocket. In Nanao, a man giving us directions to the local hot springs, then coming after us half an hour later on his scooter, because he had remembered that the springs were closed for construction. Later, going down the wrong remote road on the way to a train station, and having a mother and daughter stop and offer to drive us wherever we needed to go; offer to take us to an alternate hot spring, to an alternate town, to an alternate train station (because the one we were headed to wouldn't take us Town X); offer to host us in their aboriginal village. In Hualien, stopping for dinner at a street-side restaurant where no-one spoke English, only to have a passerby stop his scooter to have a conversation and help us out (a Los Angeleno who was back in Taiwan for military service); turned out to be a Buddhist restaurant with excellent vegetarian cuisine.

The next day, waiting for a taxi to the train station, a passerby introducing himself, asking where we needed to go, and informing us that taxis were rare, but he'd be happy to drive us to the station (or the next town, if we wanted--they have a great beach there, he said). In Taroko, monks under a pagoda insisting on sharing their lunch with us, delicious honey-bread dessert included... they were returning to their monastery after visiting a friend, and had plenty, they said. Never having to wait for more than one or two vehicles to pass before getting picked up for a hitched ride. Having one older man who hitched us and spoke little English take us back to his home and his family, where he insisted on serving us lunch; "so young," he said, when we told him our age... how I wished I could ask him what he had been doing at twenty-five--what his dreams had been, what he laughed at, what he thought of how life had turned out... but all I could do was touch my beer can to his, and drink.

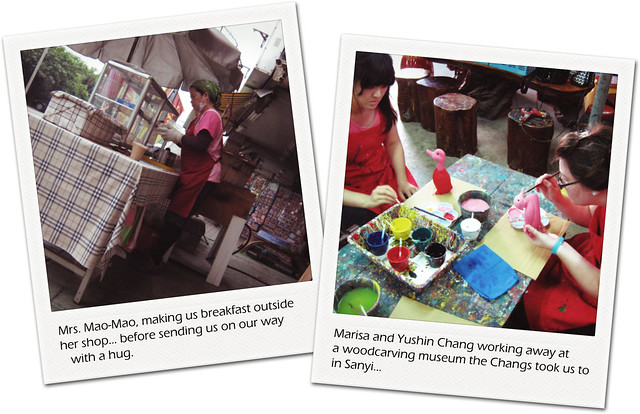

Then there were the Mao-Maos and the Changs, Taiwanese families who hosted us for three nights in Tainan and Taichung, respectively, and treated us like long-lost family members--despite knowing nothing about us except what I'd posted on CouchSurfing.org. For our arrival the Mao-Maos prepared a special meal of chicken-feet and ginger rice, and in the morning Mrs. Mao-Mao wouldn't let us leave the house until we had been properly filled with rice balls and milk tea. On our second night with them, Mr. Mao-Mao insisted on taking us to an area of Tainan which we hadn't managed to get to, treating us to "special food," and attempting to show us his favorite sights (despite the fact that it was unfortunately late on a weeknight, and most places were sadly closed). Two days later we stayed with the Changs, and despite having only twenty-four hours with them, they managed to take us to more than half a dozen locations in Taichung and Yanli and stuff us to overflowing with delicious Cantonese and Hakka foods and deserts--absolutely refusing to let us pay for anything, they went so far as to give us presents for Marisa's parents (whom we were soon to meet in Vietnam), and when we left wouldn't let us get on the train without a packed dinner--and hugs all around.

As our train chugged towards Taipei and I ate of my packed dinner bounty, my mind wouldn't stop spinning: who were these strangers, and why were they so kind to us? Who were these people who took us, sight unseen, into their homes, and treated us like family--who let us sleep next to their laptop computers and digital SLRs, and lavished food and gifts on us? As our train pulled into Taipei Station--a place that felt strangely like home, because we spent our first days in Taiwan there--I had no real answer. As I sit here at my parents-in-law's home, having just arrived in Vietnam, I still have no real answer. But what answer am I looking for? Part of me seems to believe that these kind folk we visited must have secret identities: that they are the Batmans and the X-Men of doing good--kind people who have planted themselves in wait for us, to achieve some special purpose. But I know that is not true--I have had too many encounters with too many kind people in too many countries, and I don't believe in Batman. No, these people are just ordinary people, and that reality is a large part of why I travel: because for every terrible story my grandmothers have related to me from newspapers or television, of physical violence, or kidnapping, or theft... for every one of those, there are two, or three, or four stories of someone in the world who's been unreasonably kind to a stranger... and it gives me hope to be part of those stories--now on the receiving side, but I hope, throughout my life, to be on the giving side as well.

"Kindness begets kindness, trust begets trust, hope begets hope"; It's one thing to see that as a nice, clichéd sentiment, but another thing entirely to experience the reality personally in a way that I can't deny. Have I experienced kindness from strangers before? Have I offered it to them? Certainly. But one forgets, I forget. Not that it happened, but the way it felt, the way it changed me... and so the sentiment becomes a sentiment once again, becomes cliché once again, and I distance myself from the most important things in life. The vulnerability of extended travel, and the encounters that come out of it, force me back to the center.

Taiwan's official tourism motto is ridiculous, but after our experience there I can't help but like it, can't help but feel that it's exactly what it should be.

I was reminded of the importance of balancing context with immediacy today, as I observed a child observing Ranbir Kaleka's multimedia installation, "He Was a Good Man." The piece itself is a fascinating one, if a bit slow-paced: we see an oil painting of a man in the foreground, intently focused on threading a needle... gradually, the painting comes to life: the man's image takes on warm tones, and we see that he is breathing; likewise, the background starts to shift, and change, revealing images from the man's youth; wait long enough, and you see the scene become a painting once again... curtains are drawn back, and shadows of observers come and go; from the background, a voice: "he was a good man." It is a subtle piece, interesting precisely for its slow pace and quiet rhythm; for its self-awareness, and its multidimensional treatment of life and art and observation.

Anyway, this child in front of me lost interest in the work "proper" somewhere between the original painting and its coming to life... whether he would have been inspired by the final act with the shadow observers is anyone's guess (though I have my doubts). He watched the image for a while, then took from his pocket a piece of transparent plastic (a magnifying lens, supplied by the museum to help with reading their miniature brochures), and walked as close to the needle threading man as he could get... lifting the plastic, he turned it this way and that, so that it refracted the light from a distant ceiling and sent it scattering across the virtual painting. He smiled, gave the plastic a few more twists, then put it back in his pocket and went sidling off to the next exhibit. His experience of the piece was different than mine; for him, the context of the work was immaterial... even its content was largely irrelevant: it was his very individual interaction with it that mattered. For me, on the other hand, context is paramount... which, I suppose, is why I'm in Taiwan to begin with.

People ask me why I can't make games about distant places from the comfort of my living room... why I need to actually travel to make games about Taiwan, or Laos, or Vietnam. As I sit here in a cramped hostel room that looks more like a dungeon cell than a livable space, my few pieces of clothing hung up to dry after a spill in the mud, I'm asking myself the same question... certainly my living room (if I had one) would be more comfortable to inhabit... certainly a desktop computer and consistent access to an internet connection (to say nothing of power outlets) would be more practical and efficient for coding games... certainly a larger wardrobe (and washing machine) would be great for when I fall in the mud. But the enterprise would be lacking context. When I can look out the window and see Taiwan, I feel Taiwan. Which is not to say that I have any illusions of knowing the place in a deep kind of way--I'm a passerby, not a resident with roots and connection--but the sense of context I get from being here is still powerful for its ability to drive and and inspire me... in that way, I suppose, its completely subjective. I don't know if I could make good games about Taiwan from a living room in Korea or the USA, and I don't know if I will make good games about it while I'm here; what I do know is that I lacked the energy or desire to start in on creating anything about the place before I got here... and now that I've arrived, I'm engaged in a way that I wasn't before. Seeing the people, hearing the language, smelling the air, getting lost in back alleys... all of it makes Taiwan feel real and three-dimensional to me in a way that paper and celluloid alone cannot. I lust for context.

Which is why I was at Taipei's Museum of Contemporary Art today. And why this post is ironic. Because I went to the museum to see contemporary art by contemporary Taiwanese, only to find that it has no permanent collection, and is currently showcasing the work of contemporary Indian artists in a collection of exhibits called "Finding India." Which is where Ranbir Kaleka and my young light-scattering friend come in. I struggled at first to find meaning and connection as I wandered through rooms full of works by Anirban Mitra, Nalini Malani, and their peers... why was I here viewing Indian artwork on one of the five days I have to explore Taipei? How was this helping me to understand or appreciate Taiwan? It's one thing to view art from India when it comes to your homeland, but how does one process art from another country, while traveling in a third?

Colors and images, names and titles passed by, and none of it meant much to me--until I saw the light scatter from my young friend's magnifying lens, and saw the look of joy on his face as he reexamined the image in front of him: the old man threading his needle, now in a shower of light. It struck me then that my preoccupation with context was doing me a great disservice... that I might be in Taiwan, but here was my chance to learn something about India, about a few of the artists who live there and what they want to express. This boy with his plastic had been getting more out of the artworks than I had, until I was able to shelve my desire for context for a while, and take in the displays on their own terms. The context of the pieces was still more important to me than it was to that boy--in terms of their Indian origin, and the artists who created them--but I was able to set aside what was for me the incoherence of experiencing those pieces while traveling in Taipei.

At the end of the day Marisa and I ended up "finding India" for over three hours, and I'm very glad we did. Later we took a packed MRT to Shinlin Night Market in order to continue finding Taiwan...

I was reading some Parker Palmer today, and something he said reminded me of Annie Dillard's weasel essay, found in Teaching a Stone to Talk. I read the essay again, and seeing as it is the inspiration for our blog's byline, I thought I would go ahead and post it here. It is one of my all-time favorite essays.

Click on the "continue reading" link to see the whole thing.

ANNIE DILLARD

LIVING LIKE WEASELS

A weasel is wild. Who knows what he thinks? He sleeps in his underground den, his tail draped over his nose. Sometimes he lives in his den for two days without leaving. Outside, he stalks rabbits, mice, muskrats, and birds, killing more bodies than he can eat warm, and often dragging the carcasses home. Obedient to instinct, he bites his prey at the neck, either splitting the jugular vein at the throat or crunching the brain at the base of the skull, and he does not let go. One naturalist refused to kill a weasel who was socketed into his hand deeply as a rattlesnake. The man could in no way pry the tiny weasel off, and he had to walk half a mile to water, the weasel dangling from his palm, and soak him off like a stubborn label.

And once, says Ernest Thompson Seton--once, a man shot an eagle out of the sky. He examined the eagle and found the dry skull of a weasel fixed by the jaws to his throat. The supposition is that the eagle had pounced on the weasel and the weasel swiveled and bit as instinct taught him, tooth to neck, and nearly won. I would like to have seen that eagle from the air a few weeks or months before he was shot: was the whole weasel still attached to his feathered throat, a fur pendant? Or did the eagle eat what he could reach, gutting the living weasel with his talons before his breast, bending his beak, cleaning the beautiful airborne bones?

I have been reading about weasels because I saw one last week. I startled a weasel who startled me, and we exchanged a long glance.